No end in sight for antibody-drug conjugate enthusiasm

One first-in-human study and two deals in a single day sees companies blaze the ADC trail.

One first-in-human study and two deals in a single day sees companies blaze the ADC trail.

With Seagen’s Adcetris and Daiichi Sankyo/AstraZeneca Enhertu firmly established in the antibody-drug conjugate hall of fame, interest in novel ADC approaches shows no sign of waning.

Yesterday, on the same day that Daiichi took yet another of its stable of deruxtecan payload conjugates into the clinic, Seagen and Nurix broke ground on ADCs based not on toxins but on degraders, while Biocytogen endorsed Myricx’s work on a novel type of payload. The work demonstrates how ADCs have become one of the most actively researched modalities in cancer drug development.

That’s quite something, for a field scarred by the 2010 withdrawal of Pfizer’s Mylotarg – the world’s first approved ADC – and the serious problems ImmunoGen encountered a few years later with faulty linkers. Notably, the FDA approved Mylotarg on new data seven years after its withdrawal, while ImmunoGen is now hitting the big time with Elahere.

But it was Adcetris – Seagen being the first company really to nail the delicate balance of ADC linker and payload – that properly launched this field, and the subsequent success of Enhertu consolidated the success.

Daiichi has continued developing ADCs using the technology that lies behind Enhertu, and yesterday said the first patient had been dosed in a first-in-human trial of DS-3939 in solid tumours. DS-3939 is an ADC against TA-MUC1, based on the humanised MAb gatipotuzumab, which Daiichi had licensed from the private German group Glycotope back in 2018.

MUC1 is a relatively well-researched antigen, with OncologyPipeline showing 24 active clinical-stage projects across several modalities. But gatipotuzumab seems to be the only one of these that targets TA-MUC1, which is an epitope claimed to be specific to cancer-expressed MUC1; thus the claim is that DS-3939 might avoid non-tumour MUC1 epitopes.

Nurix and Myricx

Deal-making saw Seagen yesterday pay Nurix $60m up front to develop ADCs that use targeted protein degradation, an expertise of the latter company, while China’s Biocytogen bought into N-myristoyltransferase (NMT) inhibition, a concept being developed by the private UK biotech Myricx.

Myricx had a poster at this year’s AACR meeting describing the NMT enzyme as a possible cancer target. The idea, however, is to use an NMP inhibitor as an ADC payload, in place for instance of the more common topoisomerase inhibitors, maytansinoids or auristatins, and Myricx says this approach has preclinically shown excellent efficacy and safety.

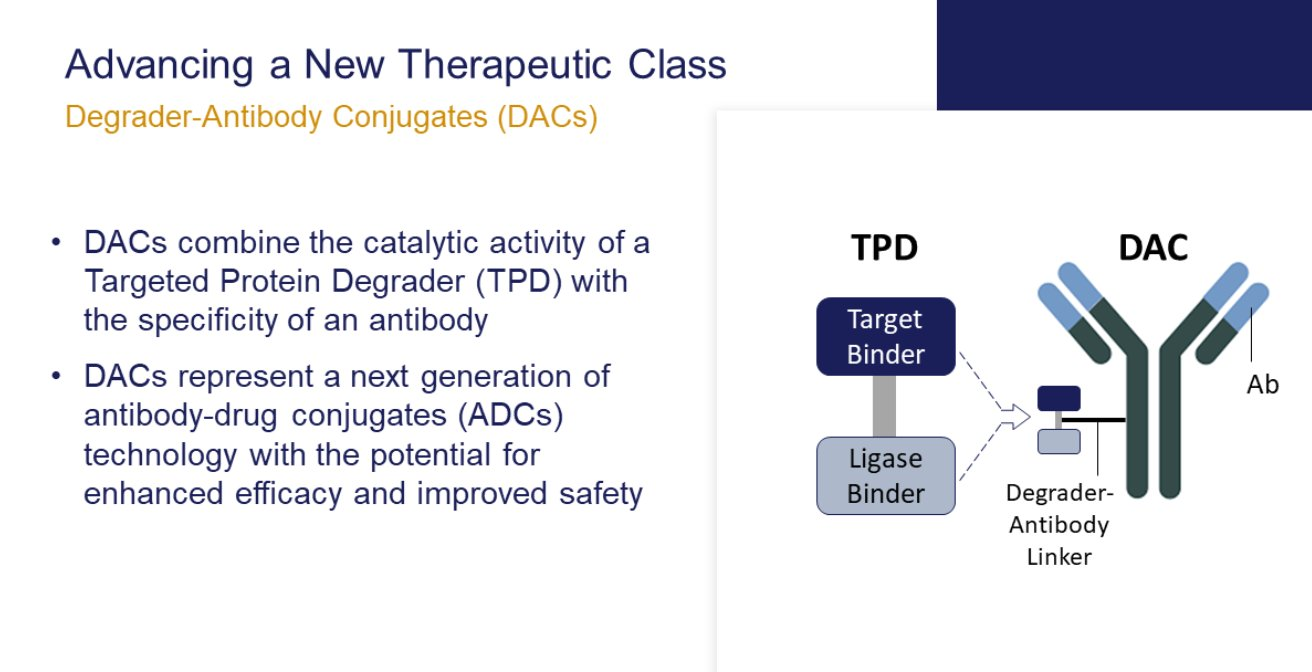

Meanwhile, Nurix and Seagen seem to be embarking on an entirely different class of ADCs, which they call degrader-antibody conjugates. Nurix’s pipeline includes oncology projects that degrade BTK and IKZF, and on an investor call the company said the Seagen deal predefined targets that were new to its pipeline, though of course the degrader part will concern the payload element of any construct developed.

Using a degrader-based payload improves selectivity, Nurix said. While this likely implies less of a bystander effect – a hot theme claimed by Daiichi to lie behind the success of Enhertu – the tradeoff is improved safety, which could result in an expanded therapeutic index versus typical ADCs, increasing also the range of tumour antigens that might be targeted.

While Seagen is being acquired for $43bn by Pfizer it has continued striking small deals, though one question is how many of these will survive after the acquisition closes. Nurix said it understood that Pfizer had reviewed the Nurix/Seagen partnership.

1064